It’s been over two weeks now since the end of the Vipassana course. Part of this time has been spent in Kathmandu processing a new Indian visa. The other part was spent at the Langtang National park, trekking in the Himalayas. High up in the silence of the mountains, there was time for a gathering of the mind which had eluded me in the city.

I didn’t actually know very much about Vipassana or how it was taught before I signed up for the course. This was deliberate on my part. I had met quite a few people in Goa who had undertaken one of the ten day courses who would have been more than happy to share their experiences, but I felt that the less I knew, the less expectations or preconceptions I would have.

Certainly, there are many types of meditation out there to choose from. From Tantric to Kundalini, from chanting mantras to using movement. Each one seeks to calm and focus the mind. Vipassana differs from other types of meditation in works on the deepest parts of the mind, the subconscious, rather then focusing on the conscious mind, as the others do. Vipassana was in fact the method which the Buddha used to reach enlightenment, and is the technique which he taught his followers. Many thousands of people in Northern India became enlightened by practicing Vipassana and continued to do so, even after the death of the Buddha. But over time, it was mixed with the traditions of other meditation techniques, which led to the purity of the technique being lost to India and the rest of the world. Only in Burma was the technique maintained in its purist form. And it was through a Burmese-born Indian man, S.N. Goenka, who studied the technique intensively with his master in Burma for 14 years, that Vipassana was brought back to India in 1969.

And so on the morning of 14th April, I joined the queue along with 159 other men and women at the Nepal Vipassana Centre’s city office and began the registration process. Documentation in order, we were ushered into a grey, windowless basement room where we sat on cushions placed in orderly lines. Men on one side, women on the other. As the teacher began to intone the rules and regulations of the course, first in Hindi and then in English, I began tentatively to question my being there. Did I really want to spend 10 days of my life locked away in meditation? I knew deep down that I did.

For ten days we would agree to live by the five precepts: no stealing, no lying, no sexual misconduct, no killing, no intoxicants. We were to be in complete silence from after dinner that day. There should be no writing of notes, no gestures and no eye contact. The only people we could speak to were our teacher, the volunteers and other members of staff. We would be meditating on average for 10 hours a day, with the day starting at 4am and ending at 9,30pm. We would have three meals a day: breakfast at 6am, lunch at 11am and a snack at 5pm. The list of prohibited items included reading and writing materials, mobile phones, iPods, cameras and laptops. Yoga was also a no-no, on the basis that exercise space was limited and of the potential for it to disturb the energies of the meditator.

With the rules made clear, we were loaded onto mini buses and brought to the meditation centre, located about 12KM from the centre of Kathmandu. The atmosphere as we travelled was subdued. People sent final texts, looked at pictures of loved ones on their phones, stared into space or looked out the windows, as if to absorb as much of the outside world as possible before being entirely cut off from it for ten days. On arrival, we handed over our passports, money, credit cards and all our other contraband items. We were then assigned dorm bed numbers and seat numbers for the meditation hall. If we wished to identify ourselves to the management, we were to use these numbers rather than our names. Bit by bit we were losing our identities. As the red-painted heavy iron main gate of the complex clanged shut, the thought that we had entered a ‘concentration camp” came to me. I smiled at the black humour. True, we had all chosen to be here to “concentrate” and to gain mastery over our minds, but could it be that our lives would somehow resemble that of those prisoners who had lived in such camps during WW2? Living in segregation in a small, austere, enclosed campus, cut off from society, with no musical or artistic stimulation and with free will at a minimum, perhaps there was some minute comparison, however tentative? Without meaning to cause any offense or minimise the experience of those detained in such a way, of course.

Over a simple Nepali-style dinner, complete with Dahl Bhaat, which was to be our daily fare, I briefly got to know my dorm neighbours – Justyna from Poland and Barbara from Germany. Then it was time for silence to descend and the meditation to begin. Goenka describes the 10 day meditation retreat as a “deep operation of the mind”. For nine days the mind is dissected and then on the tenth, it is put back together. This is how he explains the process in one of his nightly video discourses.

For the first three days, we focused on our breath, using a technique called Annapana. The aim is to focus on the breath and how it interacts with as small an area as possible above the upper lip. After these initial three days, the focus moves to sensations in the body, starting from the crown of the head and working all the way down through each body part.

As predicted in Goenka’s nightly video discourse, my mind rebelled completely during the first three days. It did everything it could to distract me from my task. I would find myself thinking about the past, so I would shake myself and refocus on my breath, but seconds later, I would catch myself in the future. On and on it went, seemingly endlessly. It was like watching a video of my life being fast-forwarded and rewound at speed, over and over again. Exhausting. I feared a little for my sanity. But by the end of day three, having sought out my teacher’s advice and having finally properly understood Goenka’s instructions, I “made friends” with my mind. I called her Bernie. She looks a lot like “Mrs Brown” from the TV series, “Mrs Brown’s Boys” and has a cheeky glint in her eye, especially when she knows that she’s just played the old “here’s a cute memory to pass the time” trick on me.

As Bernie and I got to know each other better, the meditations got a little easier. When I would catch a thought coming into head, I would smile, shake my head ruefully at Bernie and she would slink smilingly away. This was a relief, as the daily schedule was onerous. At 4am the wake-up gong would sound, and by 4.30am we would be seated in the meditation hall for our first meditation. This two-hour morning meditation was always the most difficult one for me. It was bitterly cold for most of our time at the centre, especially in the mornings and evenings, and I had a hard time keeping warm. Having had our last meal of the day at 5pm, a snack of rice crispies, fruit and tea, my tummy was generally rumbling by morning. Sitting on my cushion wrapped in the regulation green tartan blanket, I would start the session with great intentions, but 20 minutes later, I would feel a tug on my cushion and a whisper in my ear – a volunteer encouraging me to wake up and straighten my back. I would try again, only to once again find myself slumped forward, my head making friends with my feet. My teacher tried to help me by explaining that this tendency to sleep was linked to resistance and anger and I should become aware of these emotions and fully integrate them into my meditation. Hmm. I would try.

At the end of day three, just when I thought I was getting into the swing of things, my stomach started acting up. This was nothing new for me. We were eating a typical Nepali diet, rich pulses, so I wasn’t at all surprised that my body was rebelling. I figured I’d bear with it and I’d come around in a couple of days. I was also aware of the body-mind connection factor and figured that all the stuff being processed by my mind was having an effect on my body. But on and on it went, day after day. I took the few meds I had and tried fasting on day five, but to no avail. On day six, finally admitting that perhaps I needed help to stop the cramping which was proving to be a big distraction in meditation, no matter how much I tried to deter my thoughts from it, I finally approached one of the volunteers with my problem. She was incredibly helpful and had the kitchen prepare big plates of “water rice” cooked in turmeric for each of the meals to help settle my stomach. Although I was hugely grateful for her help, there were times when I felt completely despondent when I would see the plate of rice arriving. So much so, I could feel tears forming. I longed for a bowl of tomato soup and some dry toast. But in signing myself into the meditation centre, I had effectively given up my right to make such choices. For those 10 days, the course being run on a donation basis, I, along with all the other participants, had become a Buddhist nun. We were fully dependent on the kindness of others for my food, lodging and well being. This is done very deliberately for each Vipassana course, as by surrendering in this way, a breaking down of the ego begins.

But the turmeric rice and special herbal drinks which were prepared for me with such care failed to work their magic. By the morning of day eight, I felt like I could take no more and I asked to see a doctor. I knew I needed antibiotics if I was to finish the course and I was absolutely determined to do so. As luck would have it, there was a doctor volunteering on the next course, who had already arrived at the centre and I was brought to see him. He quickly administered rehydration salts and antibiotics. I was so grateful to him. By the afternoon I was feeling myself again. It was as if a cloud had been lifted off me. Meditation felt easy again and I found myself looking forward to the sessions to follow that day.

It was during the afternoon session on that eight day when things somehow came together for me. Gone was my resistance to sitting. If my knees, hips or back were aching, then I was not aware of them. My mind became very still and very clear. I could flow easily through the sensations in my body. It felt like my skin and my insides were pleasantly fizzing and popping. And then something lifted out of me. I have no idea what it was exactly, but some great weight from the depths of me was released. I felt a great rush of energy. My spine, neck and head stretched to their maximum and I felt as if I was heads taller than anyone else in the room. My breathing became laboured and I was sure that a volunteer would soon tap me on the shoulder and ask me to keep it down. Whatever it was kept coming up and up and up, until finally all of it was released. My breathing calmed and my posture normalised. I felt at peace. I felt intensely happy.

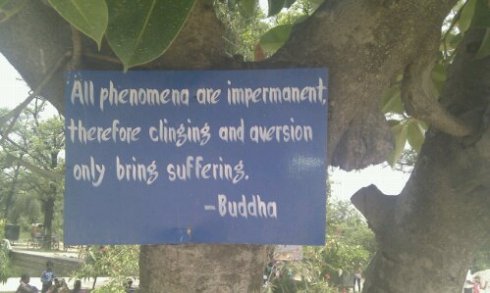

After this experience, for the remainder of the course, my meditations were peaceful, happy events. I even looked forward to the hour-long “Strong determination” sessions, where all movement was discouraged. Whereas before these sessions would evoke deep sighs and sometimes even tears of frustration from me, my mind jumping from one thing to another, now I sat in complete peace. Images of people who I felt at times of my life had somehow wronged me, flashed through my mind, followed by a deep forgiveness to all. I had come to a place where I fully, finally understood the nature of impermanence, which forms the basis of Vipassana. Of course I had been aware of this concept before starting the course, but it was through the struggles I had gone through over the 10 days that full consciousness of impermanence finally manifested. This peaceful, balanced, “equinanimous” state of mind is what I had come looking for and I was so grateful to experience it.

On day ten we were finally allowed to begin speaking again. The campus filled with excited voices and there was an air of festivity. We had come through our ordeal in one piece and now it was time to re-join the world. We shared our experiences, collected our passports, cameras and laptops, and took our last meal together. Soon we were back on the buses headed once again for Kathmandu. Most of us were anxious about being back in such a chaotic place after the peace and tranquillity of the meditation camp. But through his final discourses, Goenka had prepared us well. He advised us that we had taken the first vital step towards awakening. Our task now was to each day practice maintaining a balanced mind, no matter what the situation. He told us to observe ourselves and to see that nine times out of ten, we would react in our usual way to a given situation, but if on that one other occasion, we were able to stop in our tracks, observe our breathing for a moment and then choose to behave in a different, more balanced way, then the technique is working.

The road is long, he says, but with constant and committed practice of the technique, anyone can leave misery behind, release past “sankharas” to achieve a higher level of consciousness and live a better, happier, more balanced life. The equation is simple: if you are happy and are putting the best of yourself into the world, then others around you will be happy and the world will be a better place. His advice is to meditate for two hours a day – one hour in the morning and one hour in the evening. It sounds like a tall order, but for the benefits it brings, it is certainly worth the effort.

For more information about Vipassana centres in Nepal, see: http://courses.dhamma.org/en/schedules/schshringa

For information about Vipassana meditation in Ireland, see: http://www.ie.dhamma.org/index.php?id=ie_.html

For information about course in the rest of the world, see: http://www.dhamma.org

Newspaper article about Vipassana in Nepal: http://nepalitimes.com/news.php?id=19805